IWG: A +20 % Growth Undervalued Compounder Trading at 6× EV/EBITDA

Deep dive on this flex space value play

Here I present a company trading at a bargain valuation that guides to high double digit profit EBITDA and FCF growth, with little debt and founder led, poised for a breakout in growth and shareholder returns in the coming years.

Investment Report on International Workplace Group (IWG)

International Workplace Group is not exactly undercovered, but it remains largely undervalued. Although many analysts have labeled it a value trap—citing management’s missed targets, lingering skepticism about the leadership team (despite its founder-led structure and a 25 percent insider stake), and other concerns—the underlying data tell a different story. Trading at just 6 EV/EBITDA, shifting toward a capital-light business model, and operating in an industry projected to grow at high-teens rates, IWG looks exceptionally compelling. With accelerating buybacks, emerging growth and growing operational leverage, the company may be approaching an inflection point. In this deep dive, we will examine the sector, unpack the company’s value proposition, explore its hidden moat and outline future growth prospects. After dedicating considerable time to this analysis, I believe it represents one of the most complete investment theses on IWG to date. Our conservative valuations suggest the stock could deliver multibagger returns over the coming years.

1. Introduction:

Here I present International Workplace Group (IWG), the global leader in flexible office and co-working space. Don’t confuse it with WeWork: IWG is far larger, profitable and trading at a bargain valuation. It serves millions of users across more than 3 500 locations in 120 countries, operating under 19 brands—including Regus, Spaces, Signature and HQ. According to Fortune Business Insights, the global flexible-office market was roughly $35 billion in 2023 and is expected to reach $96 billion by 2030, a compound annual growth rate of 16 percent, as organizations embrace hybrid working to reduce costs and boost employee satisfaction. The company was founded in 1989 by Mark Dixon, who remains CEO with a 25 percent ownership stake. He effectively created the sector and has steered it through both the dot-com bust and the 2008 recession.

At its core, IWG leases office space on long-term contracts, then subleases smaller units at higher per-square-foot rates by dividing those premises into individual offices, coworking desks or flexible-space suites. Crucially, it owns no real estate; like Airbnb or Uber, it acts as both the software platform and the marketplace, while also operating most of its locations. More recently, IWG has begun adopting an even more capital-light model: franchised and managed sites where it neither holds the lease nor invests significant OPEX or CAPEX.

IWG’s brand recognition, reservation software and operational scale deliver outstanding margins. By contrast, small operators struggle: nine out of ten coworking ventures lose money in their first year, and nearly half remain unprofitable after four to six years. Regus, by comparison, can achieve 25 percent contribution margins and mature a new location in under eighteen months.

2. The flexible office market and IWG business model

The flexible office market has come a long way over the past decade, and who better to explain that evolution than IWG’s founder, Mark Dixon? I stumbled upon a Bloomberg interview from ten years ago in which he lays out the origins of the business model.

Back then, coworking and flexible offices as we know them today did not exist. People split rent informally to save money, but there was no Regus or similar network. As laptops and smartphones became ubiquitous, many began working from coffee shops, yet most still preferred a dedicated office. Renting a full office long-term was prohibitively expensive for an individual who only needed it sporadically. A space available by the day—or a small section of a larger office—suddenly made perfect sense. Business travelers who previously held meetings in cafés or restaurants, including Bloomberg’s own staff, could now access professional facilities in any city.

In that interview, Dixon revealed a striking strategy: he aimed to double Regus’s footprint in Spain and Greece, two economies then in crisis. His reasoning was that when budgets are tight, people are more willing to try new solutions. He argued that the company actually grew stronger in weak economies and plateaued when markets were booming. Watching the full conversation today, it’s remarkable how accurately he foresaw the impact of flexible work on the office landscape.

Fast-forward to last year’s interview and the narrative has shifted significantly. Rather than working from cafés, many employees now prefer home offices, a trend accelerated by COVID. Employers, however, have pushed for a return to the office. Flexible workspaces offer a middle path: employees gain access to a local office without a long commute, and companies reduce their real-estate costs while preserving the productivity and collaboration benefits of an office environment. This is precisely where IWG sees its opportunity. As traditional leases expire over the next few years, the total addressable market for flexible space is expanding rapidly. According to Dixon, we are already witnessing a wave of conversions: high-cost city-center offices lie empty as workers demand hybrid arrangements and neighborhood workspaces. Flexible offices are no longer a novelty—they are becoming a strategic imperative for both employees and employers.

Cyclicality, is this something only startups and freelancers use?

Cyclicality has long been a concern in the flexible-office sector, since its client base was once dominated by startups and freelancers—groups that tend to tighten budgets or disappear altogether when economic headwinds arise. A decade ago almost ninety percent of users fell into those categories, with only negligible representation from mid-sized businesses or large corporations. Today, however, the mix looks very different. According to KBV Research, corporate clients made up twenty-seven percent of the market in 2023, while SMEs and startups accounted for thirty-six percent and freelancers and other users comprised the remainder. Argus data suggest an even greater tilt toward SMEs and large enterprises, reflecting IWG’s ability to serve bigger accounts and its concentrated marketing efforts: the company now counts eighty-five percent of Fortune 500 firms among its customers.

This shift from a freelancer-heavy model to one more evenly balanced with stable corporate and SME relationships should significantly damp cyclicality and strengthen the business proposition over the economic cycle.

IWG Business model.

IWG’s profitability rests on the spread between the long-term leases it signs with landlords and the short-term contracts it offers to end users. By dividing large office floors into smaller suites, coworking desks and meeting rooms, IWG is able to charge a 25–30 percent premium over conventional office leases on a per-square-foot basis. That premium is justified by the flexibility these spaces provide: growing companies can expand or contract their footprint quickly, and organizations facing cyclical pressures can adjust headcount without being locked into a decade-long lease. In today’s fast-changing business environment, where traditional ten- to twenty-year agreements leave space underutilized, IWG’s model aligns cost with actual need and enables savings even after premium pricing.

Satellite offices, often located in suburban or secondary markets, further enhance the value proposition by combining lower rent costs with the convenience of a local workspace. Studies suggest that employees working closer to home—free from lengthy commutes but still outside the distractions of a home office—enjoy higher productivity. In effect, IWG delivers the best of both worlds: the autonomy and comfort of remote work alongside the collaboration and structure of an office environment.

Although full-scale adoption of flexible offices remains in its early stages, IWG’s founder, Mark Dixon, envisions these spaces eventually representing as much as one-third of total office stock—implying a potential addressable market of up to two trillion dollars. Even without reaching that extreme, the current market opportunity is ample for IWG to continue growing into a major real-estate force.

The company organizes its operations into three main business segments: owned locations, which it leases and operates directly; franchise and managed partnerships, where local landlords bear the real-estate risk in exchange for IWG’s brand and operational expertise; and Digital & Professional Services, encompassing platforms like The Instant Group and virtual-office offerings. In the following sections, we will examine each of these segments in greater detail.

Owned & leased locations

Owned and leased locations account for more than 80 percent of IWG’s portfolio. In these centres, IWG signs a long-term lease, fits out the workspace and then sublets it on shorter agreements, allowing the company to capture the full unit economics of each site. At maturity, conventional centres typically deliver mid-20s after-tax ROIC. The trade-off is that build-out costs run about £590,000 per centre, meaning that adding over 1,000 new locations each year would require IWG to raise several hundred million pounds of debt or equity annually.

The gross profit contribution from owned and leased centres has remained robust, with a modest year-over-year increase since the COVID downturn. Despite the addition of a few new sites last year, the overall number of conventional locations held steady and total revenues from this segment were essentially flat, suggesting limited upside in growth from these assets alone.

IWG’s primary growth engine in the coming years will be its shift toward a capital-light model, driven by managed partnerships and franchise agreements. By opening roughly 1,000 new spaces annually through these arrangements, the company can avoid the large upfront capex required for traditional leases, boost free cash flow and mitigate balance-sheet risk. Moreover, capital-light operations tend to attract higher valuation multiples, reflecting their leaner investment requirements and more predictable returns.

Franchise Model Explained

Under its franchise structure, IWG grants Master Franchise Agreements that give local operators exclusive rights to develop and run centres within defined territories. While the company signed agreements in Japan, Switzerland and Taiwan as recently as 2019, the pandemic paused new franchise roll-outs; today IWG favors its managed-partnership model for its superior returns. Franchisees assume virtually all build-out and operating costs, allowing IWG to earn more than 80 percent margins on the fees it retains. In its Japanese MFA deal, for example, the upfront consideration equated to about 3.4 times first-year revenue, with ongoing royalties of 4–5 percent—a multiple that surprised many analysts but underscores the strength of the IWG brand and its global network. Publicly available terms for Regus franchises generally reflect similar economics: a one-time fee of around $20 000, royalties of roughly 6 percent, a 2 percent marketing contribution and an initial investment ranging from $700 000 to $1.5 million.

Managed Partnership Model Explained

Managed partnerships involve IWG directly managing flexible office spaces on behalf of landlords, without leasing the space itself. Landlords directly lease to flexible tenants, paying most of the upfront and ongoing capital expenses, plus operational costs. They benefit from higher rental premiums (20-30% above traditional leases), despite shorter-term leases, making it profitable even after fees. Landlords typically pay IWG an upfront fee (~£17,500 per site) and an ongoing royalty averaging 15.5% of revenue. Due to its superior profitability and reduced capital requirements, IWG now prioritizes managed partnerships, planning for these to represent over 90% of annual location growth.

Across advice blogs aimed at independent landlords and small-scale workspace operators, the consensus tilts toward revenue-share or management contracts rather than classic franchising. Optix’s primer argues that management agreements let property owners keep the asset, start cash-flowing sooner and shoulder far less capital risk than a Regus-style franchise, whose up-front fees and 6 per cent royalty can erode returns Optixsharpsheets.io. Coworks echoes this view, calling management deals “a partnership that fills vacant space and splits the upside” while avoiding the long leases and large fit-out bills a self-run centre would require coworks.com. Deskworks’ three-part operator interview adds that management contracts are “the big motivator” for owners who want to expand with “minimal out-of-pocket capital,” though it warns they yield a smaller slice of profit per site and demand strong automation to scale efficiently Deskworks. Even landlord-focused guides such as Nexudus and Denswap stress that revenue-share models boost rent per square foot by 20–30 per cent and align operator and owner incentives over the long term Nexudusdenswap.com. By contrast, franchise reviews point out that while a brand licence delivers turnkey systems and marketing power, entry costs of roughly US $0.9–1.9 million plus 4–8 per cent ongoing royalties make profitability harder for first-time owners franchisechatter.com. Taken together, these sources suggest that smaller landlords seeking lower risk and faster cash flow usually favour managed agreements, whereas those who value brand reach and are comfortable with heavier fees may still opt for a franchise.

As property owners recognize the advantages of management agreements, they are increasingly aligning with IWG’s strategy. Small operators, by contrast, face a host of challenges when launching on their own. According to a DeskMag survey, only eleven percent of coworking spaces turn a profit on day one, and just sixty-eight percent achieve profitability after four to six years.

Not a big surprise, but most coworking spaces that struggle to attract customers remain unprofitable, whereas venues without occupancy issues perform markedly better. In other words, the central hurdle for small operators is customer acquisition—precisely the problem IWG’s scale, brand and technology are designed to solve. Given that this survey was sponsored by two software providers serving independent operators, actual profitability rates may be even lower than reported.

Persistent losses and thinner margins will ultimately price smaller players out or compel them to enter franchise or management agreements. That dynamic plays directly into IWG’s hands, reinforcing the logic of its capital-light model. With these tailwinds in place, it is entirely plausible for the company to open a thousand new locations annually.

In the latest full year 2024, IWG delivered a 17 percent increase in total system revenue—reflecting its managed partnerships and franchise operations—with 185 000 rooms across 1 116 centres. Remarkably, half of those locations came online during the year, and another 725 centres (matching today’s room count) are already signed and ready to launch. That backlog alone is more than sufficient to double the contribution from this segment, since every penny of fee income flows directly to gross profit.

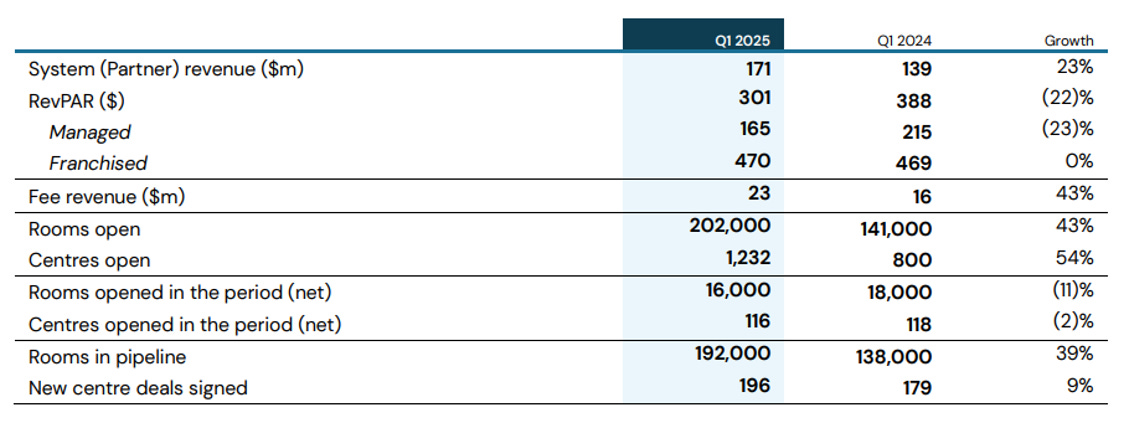

This momentum carried into Q1, where system revenue rose 23 percent, fee revenue climbed 43 percent and the number of rooms in service and in the pipeline expanded by 40 percent. As newer spaces mature and RevPAR stabilises (currently depressed by the ramp-up of unproven locations), fee revenue should accelerate further. At present, the company is opening roughly 15 000 to 16 000 rooms each quarter—equivalent to about 120 centres—while the developing pipeline now stands at 192 000 rooms, sufficient to deliver more than 1 000 new locations.

Digital & Professional Services (Worka)

IWG’s Worka segment brings together its suite of digital platforms, led by The Instant Group, in which IWG acquired an 86.6 percent stake for just under £270 million in March 2022. The Instant Group runs the world’s largest independent workspace brokerage at instantoffices.com, where roughly 90 percent of bookings last one year or less, reflecting a predominantly startup and SME customer base. It generates revenue through a 10 percent commission on each booking and by selling aggregated market-intelligence data. Its managed-partnership arm mirrors IWG’s core model: landlords fund fit-outs, The Instant Group provides marketing and operations, and both parties share the resulting income.

Davinci Virtual, another key asset in Worka, offers virtual-office services—business addresses, mail handling and call forwarding—at very low incremental cost, resulting in high margins and strong customer retention. Under IWG’s segment reporting, revenues and profits from all virtual-office services are split equally between Core IWG and Worka. Smaller platforms such as HometoWork, Rovva and Meetingo further diversify the digital ecosystem.

Despite high expectations, Worka’s revenue and profitability performance has disappointed some investors. Although revenues rose modestly after the acquisition, they plateaued last year following the loss of a major contract. Many of the platform’s benefits do not appear in segment-level KPIs, since income from these services is shared equally across Core and Worka. That arrangement allows IWG’s own operations to avoid the 10 percent commission that competitors must pay and thus boosts system-wide profitability. For example, in managed locations where a partner pays 15 percent of revenue to IWG, other operators would need to allocate roughly two-thirds of that amount just to secure bookings. This built-in advantage should give IWG greater pricing flexibility and a sustained edge as the platform scales and more locations come online.

3. Office commercial real estate booms and busts.

Office commercial real estate is notoriously cyclical. When demand outpaces supply, developers break ground on new projects—driven by optimistic forecasts for rents and occupancy—but those buildings often take three to five years to complete. By the time they open, market conditions have shifted, vacancy rises and rents fall below expectations, triggering distress sales and further downward pressure on values. Although IWG does not own the buildings themselves, its long-term leases expose it directly to these swings: rising market rents push up lease rates when spaces roll over, squeezing the profitability of new coworking centres.

Today’s office market faces an even harsher downturn. Beyond the familiar oversupply problem, many landlords financed their developments with interest-only loans that come due in full upon maturity. Under normal conditions, refinancing would be routine, but with high vacancies and falling rents it has become far more difficult—and delinquencies on office-sector loans are climbing. According to CommercialEdge, average office utilization remains roughly half of its pre-pandemic level, while vacancy rates have climbed to record highs and continue to worsen.

Employees increasingly resist commuting long distances into city-centre towers, and employers—from startups to global corporates—are realizing that they can save millions by reducing traditional office footprints in favour of remote work or flexible suburban hubs. This shift not only deepens the challenges for conventional landlords but also underscores the value of IWG’s flexible model, which can adapt to changing demand and avoid the fixed-cost burden that comes with traditional leases.

Office Properties Income Trust exemplifies the office space crisis. This specialized REIT set out to finance high–credit–quality tenants and build an on-book asset base of $3 billion, backed by $2.3 billion in debt that now must be refinanced on unfavourable terms. I seriously doubt the portfolio warrants a $3 billion valuation—just consider the properties they pledged as collateral to secure $445 million in loans.

They report a net operating income of $50 million against nearly $1.3 billion in book value, implying a 4 percent cap rate for office assets. In today’s market that is wildly optimistic; at a more realistic 6–7 percent cap rate, the company would be deep in negative equity. The stock price already reflects this mismatch. Yet their bonds trade at pennies on the dollar, which may offer an intriguing risk-return opportunity.

Is flexible office the winer in the office real estate crisis?

The distress in traditional office markets has created a clear opening for flexible-space operators, and IWG stands to benefit disproportionately. As vacancy rates soar and landlords grapple with falling asset values, many are reconsidering the decades-long lease model and turning instead to partners who can offer turnkey coworking and serviced-office solutions. In the past, landlords were wary of subleasing to flex operators or shouldering the fit-out costs themselves, but today they are not only willing to sign leases with IWG and its peers, they are even contributing capex to convert empty towers into neighbourhood-scale hubs.

The numbers bear out this shift. Global flex-space revenue has expanded from roughly $32 billion in 2019 to an expected $45 billion by 2025, and penetration in premier markets such as London has climbed from 6 percent to 10 percent over the same period. Although U.S. penetration remains under 2 percent, a wave of lease expirations and enduring work-from-home preferences suggest that legacy landlords will increasingly hand over space to flex operators rather than pursue long-term tenants.

Industry forecasts confirm that flex-space is seizing market share: after a 7 percent CAGR in the decade to 2020, growth is projected at 15–20 percent annually through 2030. JLL expects the flex segment to grow from 2 percent of total office stock in 2020 to 13.3 percent by 2030, while CBRE sees potential for ultimate penetration above 30 percent. Crucially, nearly all of this expansion will come from converting existing traditional offices rather than new construction, underscoring the secular, rather than cyclical, nature of the opportunity.

Far from being a threat, the collapse in conventional office values gives IWG leverage to negotiate more favourable master leases and build out prime locations at lower cost. As landlords race to stem losses, they increasingly view flexible-space agreements not as a last resort but as the most efficient way to preserve cash flow and occupancy. In this transformed environment, IWG’s capital-light model, global brand and operational expertise position it to thrive—even as the traditional office sector contracts around it.

What happens if demand craters, down-side protection in IWG’s model

IWG structures almost every U S centre inside a single-purpose vehicle (SPV) and prefers leases that allow early “blend-and-extend” renegotiation. If demand craters, the parent can let an SPV seek Chapter 11 protection, shed or re-cut the lease and keep the rest of the group ring-fenced. This tactic has been used twice at scale and, crucially, the holding company has never entered insolvency.

Dot-com bust (2003). Regus Business Centre Corp., then losing about $2 million a month, filed for Chapter 11 along with its guarantor entities. In eight months it emerged after landlords swapped $42 million of rent claims for up to 70 million new Regus shares and accepted lower rents, leaving the group solvent and with a lighter lease book.

Covid-19 downturn (2020-21). When lockdowns emptied offices, IWG put roughly 97 SPVs—each holding one or a handful of U S leases—into Chapter 11. The centres stayed open while the court process trimmed or exited onerous leases that represented about 4 % of the global portfolio.

In both waves the aim was to stop landlord litigation, renegotiate long-term rents and preserve cash, not to liquidate. Analysts note that the flexibility of SPVs gives IWG “downside protection” compared with operators that sign corporate-level leases.

Although owners dislike having leases rejected, most still partner with IWG because it can refill space quickly. One Chicago affiliate exited an eight-storey lease via Chapter 11 and the group subsequently signed fresh space nearby; another Regus SPV that rejected a Denver lease in 2021 saw the parent take two new floors across town in 2024.

4. Competitors

IWG stands head and shoulders above its competitors in the flexible-office space. The most notorious rival, WeWork, collapsed spectacularly under the weight of its own growth ambitions and mounting losses. Ironically, WeWork’s implosion helped IWG by reducing overall supply and even allowing it to bring some of the vacated locations into its managed-partnership network. Although WeWork has since restructured under the ownership of its creditors, its recovery has been halting at best—and every struggling WeWork site only creates another opportunity for IWG to expand.

Another rising contender, Industrious, was acquired by CBRE for roughly $800 million. Industrious has built a profitable, corporate-focused operation that contrasts with WeWork’s rapid growth and high burn. Under CBRE’s wing, Industrious could scale quickly and become a more formidable challenger, but its emphasis on enterprise clients leaves it somewhat distinct from IWG’s broad, multi-brand portfolio.

Meanwhile, hundreds of smaller operators continue to populate the market. Despite their numbers, these independent players face enormous hurdles: most struggle to break even, let alone achieve the scale necessary to compete on pricing or service. Their chronic underperformance only reinforces IWG’s dominant position, as landlords and customers alike gravitate toward the security, brand recognition and operational expertise that only a global leader can provide.

5. Moat

The cornerstone of IWG’s moat lies in its ability to offer lower effective costs and faster occupancy than any smaller competitor can match. When a freelancer or startup searches online for “coworking space,” IWG’s brands dominate search results and advertising channels, drawing prospects into a polished digital experience underpinned by years of customer-data insights. A solo entrepreneur comparing options will see comprehensive amenity packages and transparent pricing—components that independent providers can only replicate at higher expense, since IWG already has pre-built templates, bulk purchasing power and a sophisticated reservations platform. Even in a new market, IWG draws on regional and global data to set competitive rates and anticipate demand, whereas a small operator must learn pricing by trial and error. In effect, the trust that IWG has earned through consistent quality, seamless booking and reliable service creates a self-reinforcing flywheel: more listings attract more customers, which generates more data, which refines the network’s market-leading positioning.

For larger corporate tenants, the moat is equally formidable. No other provider combines IWG’s scale, credit strength and geographic reach, making it the obvious partner for Fortune 500 companies that need hundreds or thousands of desks across multiple countries. These enterprise clients prize the security of long-term master leases backed by IWG’s balance sheet, the consistency of global service standards and the convenience of a single contracting party. On top of that, IWG’s ancillary offerings—secretarial support, pay-per-use meeting rooms, in-house catering—boost revenue per square foot and deepen the customer relationship, further insulating the business from upstart rivals.

In short, while coworking may seem easy to launch, it is extraordinarily difficult to scale. IWG’s unrivaled distribution, data-driven pricing, brand familiarity and end-to-end operational platform create high barriers that must be cleared before any competitor can challenge its market leadership.

6. Financials:

Financial reporting has long obscured IWG’s true performance, contributing to its undervaluation. Under IFRS 16, lease expenses inflate the income statement while the corresponding right-of-use assets are merely depreciated and added back in the cash-flow statement. The result is an apparent mismatch that makes the P&L harder to interpret and causes many screens to overlook the company.

This year marks the first time IWG will report under U.S. GAAP and in U.S. dollars—changes that should make its results more familiar to—and discoverable by—global investors. Although a U.S. listing has been discussed, it remains a later priority.

Below is a link to the investor dataroom on IWG’s website. I’ve also highlighted a few key financial metrics.

https://investors.iwgplc.com/key-financials/data-book

Revenue:

The company grew strongly since the financial crisis, but plateaued for some obvious reasons during COVID, now growth should reaccelerate in the next two years with more openings and the first managed and franchised operations maturing.

EBITDA:

The company is returning to EBITDA growth, currently sitting at 557 million dollars pre IFRS (explanation below), and targeting between 580-620 million in EBITDA for FY 2025, and guidance for 1 billion in EBITDA in the medium term which I assume is 2028-2029.

Debt

Debt remains conservatively managed, sitting at just over one times pre-IFRS EBITDA, leaving ample headroom for shareholder returns through dividends and buybacks. In 2024, IWG refinanced and extended its debt maturities with several key transactions. It issued a €625 million euro-denominated bond due June 2030—rated BBB (Stable) by Fitch—of which €525 million was swapped into US dollars at an 8.137 percent coupon, while the remaining €100 million carries a 6.5 percent interest rate. The Group also signed a $720 million revolving credit facility that matures in June 2029, replacing a larger $1.1 billion line. Meanwhile, the face value of its £350 million convertible bonds (originally hedged at $445 million) was reduced to £158 million (hedged at $201 million), with a fair value of $193 million as of December 31, 2024. Those convertibles are callable or convertible at £4.5807 per share in December 2027, with bondholders having the option to cash-settle at par in December 2025. After accounting for financing fees of $29 million, net financial debt stood at $712 million at year-end, modestly below the $775 million reported a year earlier.

US listing

They are not yet looking to list in the US stock market but they are changing to GAAP accounting and reporting in dollars to make their business easier to understand to investors from the united states and eliminate currency effects to the pound as more than half of their business is in the US..

7. CEO.

Mark Dixon, the founder and CEO of IWG, literally created the flexible-workspace sector. A lifelong entrepreneur who launched his first business at sixteen and bootstrapped IWG with his own capital, he still owns 25 percent of the company after selling shares to fund his lifestyle and personal interests. a move the market overreacted to but one I view as entirely benign. Doubts about his forecasts and leadership lack substantive backing. Although he has revised guidance on occasion, those adjustments were driven by extraordinary events, most notably the COVID-19 crisis. There are multiple interviews to the CEO out there so I will not expand much more.

8. Valuation

We will model the future growth of each segment, with special focus on managed partnerships and franchises, from this year through 2028.

Company-owned

For the company-owned segment, I expect minimal growth—around 2 percent annually—since the company is no longer prioritizing expansion in this area. However, I anticipate that contribution margins will rise to 27 percent as operations become more efficient and money-losing coworking locations exit the market.

Managed and franchised

I based my assumptions for the managed and franchised segment on two key observations from the company’s presentation and data set. First, it takes approximately 1.5 years for a newly opened room to reach maturity. Second, mature rooms currently generate around $3,800 to $4,000 each, according to IWG’s projections and results from established centres. With 202,000 rooms already open and 192,000 in the pipeline, system-wide revenue should total about $1.5 billion once these spaces are fully operational. In my model, I assume immature rooms earn $2,500 each, that maturity takes 1.5 years, and that IWG opens 134,000 rooms this year (per its guidance) followed by 150,000 rooms annually thereafter. Although this pace is below the company’s stated targets, I believe it is a conservative estimate.

Digital and professional services.

For the Digital & Professional Services segment, I have adopted a cautious outlook. I forecast a 20 percent revenue decline this year due to the lost contract—likely overstating the drop—and assume minimal margins at cycle-low levels. From there, I model a gradual recovery with 10 percent annual revenue growth and improving margins. I will also adjust for the 13.4 percent of Worka still owned by the acquired company’s management team, reflecting the non-controlling interest in my overall valuation.

For the final model, I have added an estimate for overhead and other expenses growing at 7.5 percent, which is the only cost line we need to calculate the company’s EBITDA assumptions. Even with these conservative inputs, we reach an EBITDA figure close to management’s medium-term target.

Turning to cash flows, from 2010 through 2019 the EBITDA-to-cash-flow conversion rate averaged 70 percent. Since COVID, that ratio has been volatile, driven largely by working-capital swings across numerous locations. I expect it to stabilize going forward, and would be comfortable assuming a 60–70 percent conversion rate in the near term.

Valuing the company is challenging, as IWG stands alone at its scale and comparable transactions—such as CBRE’s acquisition of Industrious—reflect strategic, rather than financial, multiples. To remain conservative, I apply a 10× EV/EBITDA multiple, and for an alternative perspective I also use a 15× free-cash-flow multiple.

Under these assumptions, 2028 EBITDA implies an enterprise value of $8.8 billion. After subtracting $700 million of debt, the implied equity value is $8.1 billion, compared with today’s $2.5 billion market cap—equating to roughly a 3× return over three years. Using a 65 percent EBITDA-to-cash-flow conversion yields $572 million of free cash flow by 2028, which at 15× suggests an $8.5 billion equity value (and $9.2 billion enterprise value including debt).

In a bull case—where EBITDA reaches $1 billion, the cash-flow conversion ratio jumps to 85 percent as the business becomes more capital-light, and debt is fully repaid—a 10× EBITDA or even a higher multiple would produce a 4× return, potentially more if a U.S. listing drives a valuation rerating and accelerates the buyback program. Indeed, if the stock were to trade at 15–20× EBITDA upon a U.S. listing, multibagger returns would follow.

9. Risks

The most obvious risk is overexpansion: if IWG opens so many centers that they cannibalize their own margins by competing with one another, profitability would suffer. I view this as unlikely, however, since the company’s growth rate closely tracks that of the broader flexible-office market—meaning its share remains below 10 percent in our base case. A severe recession poses another challenge: revenues would decline and some locations might become loss-making. Even so, IWG should emerge from a downturn stronger than its smaller peers, whose collapse would create undersupply and fresh opportunity for the market leader. Finally, there is the chance that flexible offices simply fail to achieve the long-term adoption rates we expect and that companies revert to traditional leases. While slower growth remains possible, the combination of cost savings, employee preferences and lease expirations suggests that flexible space will continue to gain traction rather than recede.

10. Conclusion.

International Workplace Group appears deeply undervalued today, offering significant upside as growth and multiple expansion unfold. If the total addressable market eventually approaches $2 trillion, the potential upside could far exceed our 2028 forecasts.

Even in a downside scenario, it seems unlikely that IWG’s revenues and profits would decline materially from current levels, making today’s valuation attractive enough to deliver solid returns without assuming aggressive growth. There is a wide gap between market expectations and the underlying reality of IWG’s business. Its ownership of the booking platform, trusted global brand and decades of operational expertise combine to form a moat that newcomers will struggle to replicate.

As mature locations drive rising fee income, and as share buybacks accelerate, I expect the stock to rerate higher in the near term.

I view IWG as a compelling value proposition, and I will be building my position in the Buried Bargains portfolio. I plan to continue covering the company in depth for paid subscribers—so consider upgrading your membership for comprehensive analysis at less than a dollar a day.

Everything described in this site, Undervalued and Undercovered, has been created for educational purposes only. It does not constitute advice, recommendation, or counsel for investing in securities.

The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the author and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to do your own research and discuss your investments with financial advisers to understand whether any investment suits your needs and goals.