Digital infrastructure monopoly with 5–7x potential: the road to >40% EBIT margins

Deep dive on PharmX: 20 expert calls and institutional research

Today we will be looking at a monopoly payment gateway across the entire pharmacy sector in Australia. About 23b AUD in transaction volumes are routed through its system. Orders, invoices, stock feeds, everything is processed through it.

Pharmacists and other industry insiders acknowledge that if the system goes down, they have to go back to ordering with faxes and phone calls, creating a huge bottleneck across pharmacies all over Australia, because this company is integrated into the POS systems of almost all of them. This is a moat that would make some of the best businesses in the world jealous.

Yet from those 23b AUD in GTV, the company only generates around 7m AUD in revenue. And that is the opportunity. Small, profitable, with a moat that is difficult to replicate (competitors already tried), and most importantly, ready for an inflection. Why?

Because PharmX wants to take advantage of its reach and industry positioning to go from low value-added software to high value-added marketplace and data analytics products. PharmX already has the positioning, the connections, and the software is already integrated across its client base. If PharmX captured just 5% of the GTV under this new model, revenue could triple and margins could reach >40% EBIT.

The setup is simple: offer value-added services to existing customers, exercise pricing power, take a higher cut of the volumes going through the platform, and print cash by leveraging a monopoly-like position built over a decade.

The name of the company? PharmX. With a ~90m AUD market cap, it screens too small for many. The financials don’t look appealing at first sight. No sell-side analysts cover the stock, which keeps it unknown to most investors.

Today, in Undervalued and Undercovered, we will do what we know best: dissect this business down to the smallest detail. In this case, we have to disclose that we received some institutional help while researching this name: a family office gave us access to their resources in order to conduct almost 20 expert calls with insiders in the industry. Also, next week we will be meeting with the CEO to complete the coverage.

It doesn’t take a lot for the market to misprice a small cap, and in the case of PharmX there are plenty of factors that allow for that mispricing: low liquidity, zero coverage, financials that are hard to screen, one-offs that make the past look messy, and no formal guidance from management, among other things we will cover.

We think PharmX is close to an inflection point in its marketplace offering. PharmX has onboarded and signed significant clients, and it has the right positioning to succeed. Once we start seeing the marketplace become a meaningful driver of revenue, the market will rerate the company quickly, offering ample upside to early investors.

With a conservative forecast, we project that over the next 5 years PharmX could capture 7.5% of the total GTV that goes through the gateway into its marketplace solution. This would mean that, on those captured volumes, it would transition from earning a low flat fee to earning a 1.5% fee on captured volumes. That would translate into close to 8x revenue (reaching 53m AUD) and EBITDA (post capitalized R&D costs) of around 28m AUD, implying upside in the 5–7x range. And that’s before we consider the possibility of capturing a larger slice with good execution, and before we layer on the premium multiple this business could trade at if the model proves out.

PharmX’s business is crisis resilient. This is because it operates in the pharmacy sector in Australia and New Zealand. Being in healthcare, and with the Australian government subsidizing the cost of medicines, demand is relatively inelastic, which can support resilient performance even in challenging economic environments. After the dot-com bubble and the 2008 housing crisis, healthcare was one of the best performing sectors worldwide.

In addition, PharmX benefits from secular tailwinds, with the pharmacy sector in Australia and New Zealand forecasted to grow at a 7.6% CAGR through 2031.

Over this +30-page writeup, we will cover everything about PharmX:

History of the company

Business model

New product offerings

Industry structure and main players

Detailed industry workflows

Moat and possible threats to it

Fundamental bear thesis

Financials

Shareholders and management incentives

Valuation and modelling (bull and bear scenarios)

Conclusion/Execution

History of the company

Australia is a very interesting country, not only because it has some crazy wildlife, but also because of its business environment. In Australia, it’s common to see monopolistic or duopolistic positioning in key industries: supermarkets, airlines, you name it. It’s no surprise that the EDI gateway for the pharmacy sector (PharmX) is also a monopoly. This structure is rare; basically no other country looks even remotely similar. In most markets, the “payment rails” of pharmacy ordering are either owned by wholesalers or fragmented across multiple EDI gateways. It’s rare to get access to this kind of high-quality infrastructure business in public markets.

So how did PharmX manage to obtain the strong positioning it has today?

2000s: PharmX was developed as a joint venture by four leading POS providers in the pharmacy market. That structure made sense at the time because Australia is large, the supply chain is fragmented, and the pre-gateway ordering process was expensive and messy. Suppliers and wholesalers were dealing with multiple point-to-point integrations, pharmacies were forced into manual workarounds, and every POS vendor was being asked to solve the same connectivity problem in parallel. A shared gateway was the simplest coordination fix: one rail, one set of EDI standards, one place to build and maintain mappings.

That origin also explains the early network effects. Once the gateway endpoint was embedded inside the major POS systems, adoption became self-reinforcing and the gateway quickly became the default.

But the joint-venture setup also baked in conflicts and capped economics. The POS vendors wanted the gateway to exist as a neutral utility that reduced friction for their customers, not as a profit-maximising platform. They had incentives to keep pricing conservative and share economics back into the POS layer, which helped adoption but constrained earnings.

2020: Corum becomes the 100% owner of PharmX, while the litigation with Fred IT sits in the background and slowly becomes part of the story.

2021: Competitor Directo launches its B2B pharmacy marketplace.

2022: PharmX launches PharmXchange, the first real iteration of its marketplace push.

2023: Restructuring and divestments, a new CEO (Tom Culver), and a clear reorientation around the gateway plus platform value layers on top.

FY25: Revenue growth continues, but Marketplace is still early and needs rebuilding and iteration. The legal story also reaches its turning point: the Fred IT appeal outcome goes against PharmX in August 2024, forcing a repayment of 9.898m AUD. That chapter is now resolved, and the balance sheet shock was limited because the company had planned for the risk with provisions. We will explain the development and reasons for this litigation in a dedicated section later.

As you can see, PharmX’s moat was built on integration. Once the infrastructure was embedded, it had a huge advantage over new entrants. After Corum fully bought PharmX, it saw the opportunity and pivoted away from the other business lines, eventually changing the name of the listed company to PharmX and focusing the story on what actually matters: the rail, and the monetisation layers that can be built on top of it.

Business model

What exactly is PharmX?

PharmX is best understood as an infrastructure company disguised as a small software vendor. It sits in the middle of the Australian pharmacy supply chain as the data-exchange layer that makes day-to-day ordering and invoicing possible. Pharmacies do not “use” the PharmX Gateway as an app the way they use a normal SaaS product; they experience it as the invisible pipe inside their POS workflow that makes orders, invoices, confirmations, and stock messages move between the pharmacy and the supply side. The product is deeply embedded and operationally critical, to the point that any meaningful downtime would force pharmacies back to manual ordering methods.

Crucially, the gateway is not just “a gateway.” The gateway is an EDI gateway. EDI, Electronic Data Interchange, is the standardized format that lets different systems exchange business documents without human intervention. It defines what fields exist in an order, how an invoice is structured, how credits are represented, and how confirmations are transmitted. In a market where thousands of pharmacies and hundreds of suppliers all run different internal systems, EDI is the difference between scalable automation and permanent manual administration.

PharmX has already built and maintains the EDI mappings between pharmacy POS systems and a wide set of suppliers and wholesalers. Every mapping is real work: data normalization, edge-case handling, testing cycles, monitoring, and ongoing support when a supplier changes catalogue structure, a wholesaler updates fields, or a POS vendor releases a new version. This accumulated library of integrations is one of the core reasons the gateway is difficult to replicate. And it gets even harder: PharmX is the only EDI rail that allows pharmacies to process NDSS, a government program that subsidizes diabetes-related products. PharmX is the only rail that can process those orders. So PharmX is not a “nice to have.” It’s a must-have.

No one in the industry has a strong incentive to truly displace PharmX. Two competing rails are less efficient than one and rebuilding the EDI gateway from scratch would be expensive and painful for everyone involved. Fred IT is trying, as we’ll see, but so far it has not been successful in its efforts. Pharmacies confirm that it is impossible to operate without PharmX and its NDSS integration.

How PharmX makes money and plans to grow

PharmX today is an EDI gateway, with around 23b AUD in transaction flow, a monopolistic position in Australia, and a growing footprint in New Zealand. PharmX makes money by charging suppliers and wholesalers for connectivity to pharmacies. In practice, PharmX gets paid a fixed yearly fee per supplier per pharmacy connection. Based on the Fred IT litigation documents and multiple expert calls, we estimate that fee at around 20 AUD per pharmacy connection.

So yes, PharmX has a good stream of cash flow, but that alone does not justify the valuation or the growth we are projecting. So where is PharmX heading?

The answer is that PharmX is undergoing an ambitious transformation: from being “just the gateway” to becoming a marketplace and value-added layer for the industry. In other words, it is going from being an invisible rail to bundling multiple products that can support higher monetisation.

As we said, the strategy is simple. You already have 23b AUD flowing through you. The question is: what do you do to take a higher cut of that flow?

Their approach is to push four main platforms, with the goal of integrating everything together. PharmX has the Gateway, Marketplace, StockView, and Analytics. We will go deeper into each of these later, including the advantages and the obstacles, but here is a quick explanation of the key products so we can frame what the company is trying to build.

Gateway:

The gateway connects pharmacies, suppliers, wholesalers, POS systems, and government programs so orders, invoices, and claims flow automatically. Almost all pharmacies rely on it daily. If it stopped, ordering and reconciliation would largely fall back to manual processes.

“POS stacks are hard-wired to one gateway. Multi-gateway support is clunky.” (former Corum)

“If PharmX goes down, all front-of-shop ordering stops.” (Z-Software)

Marketplace:

Marketplace is the take-rate layer. It’s designed to monetize routed GTV with supplier-side fees that scale with volume. It does not need to “replace wholesalers” to work. It just needs to become the default routing layer for enough transaction flows, especially in the parts of the basket where behavior is more flexible and wholesalers have less structural control.

That distinction matters because not all pharmacy spend is equally contestable. A large share of pharmacy purchasing is prescription-linked and heavily shaped by reimbursement rules, contracted supply arrangements, and established wholesaler channels. Even if PharmX has the rail, that volume is less likely to migrate to a marketplace model quickly, and in some cases it may never migrate at all. The real battleground is OTC and front-of-shop, plus the messy exception flows: out-of-stock substitutions, secondary sourcing, short-dated deals, and promo-driven buying. That’s where suppliers want visibility, pharmacies want choice, and the “portal-first” wholesaler workflow is at its weakest.

“Marketplace is useful for independents. We joined because it gives us reach.” (Blackmores)

“We’d embed Marketplace content inside POS if PharmX offered an API.” (ZSoftware)

“Marketplace competes with POS-only ordering. It must be inside workflow.” (Corum)

StockView

A stock-availability visibility tool. It reduces failed orders and acts as a natural entry point into Marketplace ordering. If it achieves real-time, broad coverage, it collapses the out-of-stock exception workflow into a simple availability decision, a major pain point for pharmacies. Stock is not available in many cases and there is limited visibility around pricing. If it works the way it’s supposed to, it can become the default operational screen inside pharmacy procurement.

“20 out of 100 line items are out of stock daily.”

This means that if a pharmacy orders 100 products, around 20% of them would be out of stock, which means it would have to manually check other wholesalers and suppliers for those products.

“Pharmacies check manually — huge time waste.”

Analytics

Analytics is the compounding product. It monetises the data exhaust created when orders, invoices, confirmations, and substitutions get routed across the network. This is particularly valuable to suppliers who care about promotion performance, regional demand, and competitive benchmarking.

· “Suppliers want insight. Analytics is extremely valuable.”

International expansion (agreement with Toniq):

In early 2025, PharmX announced it had reached an agreement with Toniq, the leading POS vendor in New Zealand, to expand reach and offer the PharmX gateway to the 900+ pharmacies running Toniq’s POS. That effectively takes PharmX to around 99% potential pharmacy coverage in New Zealand.

It’s important to frame this correctly, because “coverage” does not mean instant adoption. The agreement does not force pharmacies to switch. It simply makes PharmX available as an option, meaning pharmacies can migrate onto the PharmX solution, but they have no obligation to do so.

Based on what management said at the last AGM, the Toniq integration work is now completed. The current focus is rollout execution: onboarding suppliers and migrating pharmacies. They mentioned adding groups like Bargain Chemist and Green Cross, and that Chemist Warehouse has already been rolled out.

If PharmX executes well in New Zealand, this can be a meaningful growth lever. Australia has roughly 6,000 pharmacies. New Zealand adds about another 1,000. That’s not a side project, it’s a real extension of the addressable footprint. There is also a synergy angle: once PharmX reaches majority penetration in New Zealand, it can connect suppliers to more pharmacies across both markets, enabling Australian suppliers to sell into New Zealand pharmacies, and New Zealand suppliers to sell into Australia, once they are integrated through EDI. That kind of cross-network connectivity is where a gateway business can compound without needing to reinvent the product.

Industry players and integration

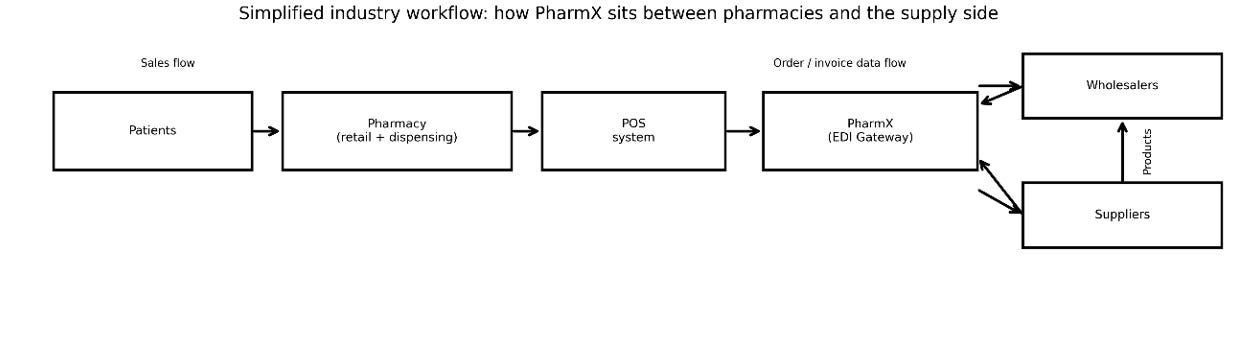

To understand PharmX, we need to understand the industry it operates in and the players in it. At a high level, the industry has four functional layers. Pharmacies sit at the edge, and almost all of them run on one of the principal POS systems. Wholesalers dominate the default ordering channel because they bundle logistics, credit, and rebate compliance.

Rebates are supplier discounts paid through wholesalers, usually tied to volume or product mix, and “rebate compliance” is the paperwork and tracking that makes sure pharmacies and wholesalers receive the right pricing and credits.

Pharmacies are a concentrated market. Roughly a third of the market sits under Chemist Warehouse/Sigma, and the rest is more fragmented. Pharmacies are key beneficiaries of PharmX: they pay nothing, get price visibility, and get cost and time savings. Pharmacies have very little incentive to stop using PharmX.

Wholesalers are also concentrated, with four major players. All of them are integrated into the gateway, but only one (the smallest) is integrated into the PharmX Marketplace. These players have a lot of power in the industry. They benefit from the gateway and happily pay for it, but they would be harmed by Marketplace and other value-add layers, because transparency compresses their margins and makes it easier for pharmacies to route orders without being forced through the portal-first workflow. We will go deeper into the workflows later.

Suppliers are fragmented. Think Pfizer, L’Oréal, and many other brands. They go through wholesalers, but they also sell independently in different ways. Suppliers benefit from price transparency, and they like the idea of selling directly through Marketplace because it lets them avoid wholesaler fees and margin leakage.

POS software companies are also a highly concentrated industry. You have a few key players like Fred, POSWorks, Corum, etc. They don’t mind the gateway because PharmX pays them a rebate for allowing the integration, and because PharmX carries the integration burden that POS vendors don’t want to own themselves.

The workflow looks like this:

The main complication is that one player operates across multiple categories. Sigma, after its merger with Chemist Warehouse, is the most important example. It sits across distribution/wholesale and pharmacy retail, and its pharmacies run on its own POS stack. It doesn’t care about the gateway because it is too small to matter to them. But what happens if Marketplace starts to compress their margins?

With roughly a third of Australia’s pharmacies under its banner, either franchised under Sigma brands (roughly 1,200 pharmacies) or owned by Chemist Warehouse (900 pharmacies), it can become a real blocker. If Sigma decides it doesn’t want a neutral marketplace layer introducing transparency and shifting economics, it has enough weight to slow adoption, restrict access, and keep that part of the market effectively captive.

Check out this video that covers the merger:

The other interesting player is Fred, one of the POS vendors that originally founded PharmX. Later on, it ended up in litigation with PharmX, which we’ll cover in more detail. For our purposes here, Fred has been trying to develop its own gateway solution, with limited success so far.

We now have a clearer overview of the industry. PharmX is integrated with all of these players.

With pharmacies, it integrates indirectly through the POS systems.

With POS vendors, it integrates as a hard-coded ordering and invoicing endpoint, plus all the error handling and business logic needed to make the workflow reliable.

With wholesalers and suppliers, PharmX integrates through EDI and catalogue normalization so orders flow cleanly and invoices reconcile inside the POS without manual work. That matters because when orders don’t go through an integrated channel, invoicing becomes a mess: PDFs and emails arrive late, don’t match the original order, credits get missed, and staff end up manually reconciling everything.

This is a big driver for Marketplace adoption. It’s not just “more suppliers.” It’s making direct supplier ordering feel simple: embedded in workflow and automatically reconciled. That removes the admin pain that normally kills direct ordering at scale.

Industry growth

Looking long term, the underlying market looks attractive, with the Australian and New Zealand retail pharmacy market forecasted to grow at a 7.6% CAGR through 2031 (based on data shared in the latest company AGM).

Workflows, incentives and players control

To correctly understand why PharmX is so important, we need to understand what problems PharmX solves for each player in the industry. For that reason, we’re going to take a very direct look at the workflows of pharmacies, wholesalers, POS vendors, and suppliers. We will look at the incentives of each group, and the benefits and threats created by each new product PharmX is launching.

Pharmacy workflows without Pharmx

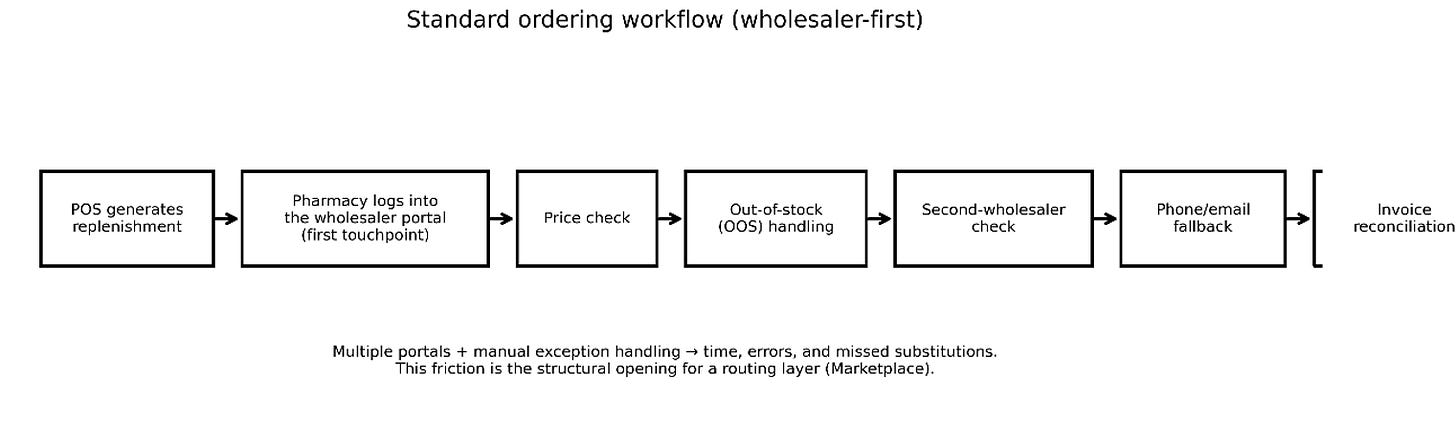

Standard ordering workflow (wholesaler-first)

In the typical pharmacy today, the POS suggests replenishment based on sales and stock. The pharmacist or staff member then logs into the wholesaler portal as the first touchpoint, checks pricing and availability, and places the order. If items are out of stock, the staff repeats the process in a second wholesaler portal or falls back to phone calls and emails to locate stock. After delivery, invoices are imported and reconciled, and mismatches often require manual correction.

This matters because it highlights the structural inefficiency that creates demand for a routing layer. When a workflow forces a user to bounce between portals and handle exceptions manually, the winner is not necessarily the platform with the best UI; it is the platform that can become the default layer that resolves exceptions without extra work.

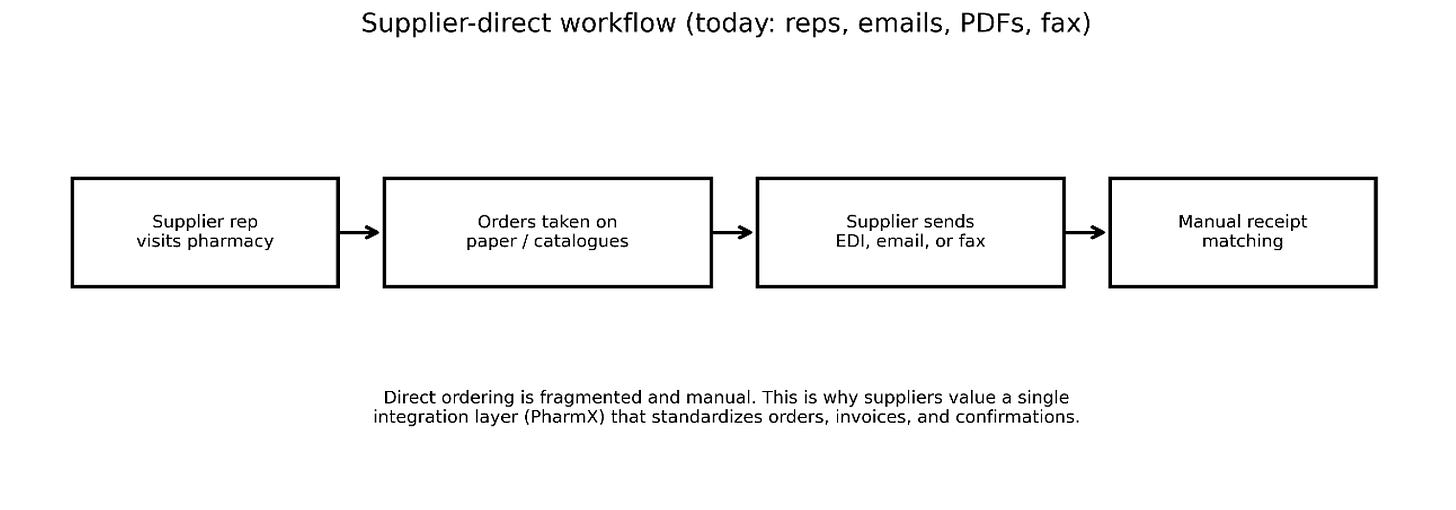

Supplier-direct workflow (reps, emails, PDFs, fax)

Supplier-direct ordering in many segments still resembles the pre-internet era. A supplier rep visits the pharmacy with catalogues or promotions, orders are taken through paper or informal channels, and the supplier sends confirmations and invoices through a patchwork of EDI, email, or fax. Receiving and matching becomes manual, and the loop between ordering, delivery, and invoice reconciliation becomes slower and error-prone.

This is the environment where PharmX becomes extremely attractive as an integration layer for suppliers. Instead of managing hundreds or thousands of one-off relationships and data formats, the supplier plugs into a standardized pipe and gains access to the pharmacy network with less operational friction.

Pharmacy workflows with Pharmx and Buy It Right

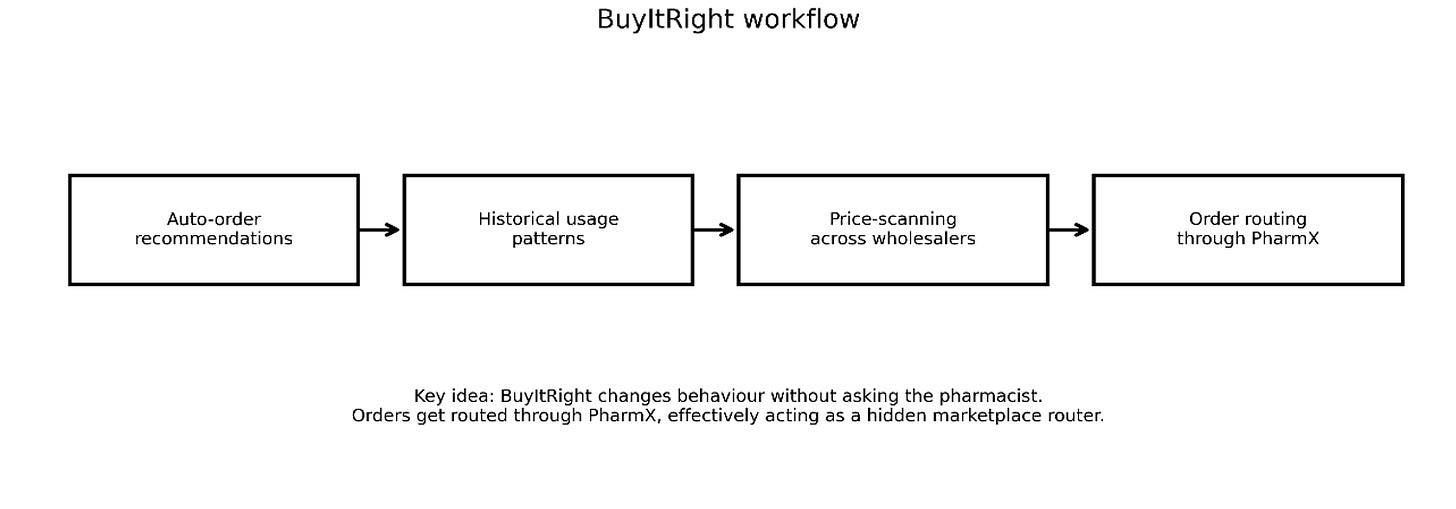

BuyItRight is important because it proves PharmX can route orders without demanding behavioural change. The workflow begins with the POS generating replenishment needs, then BuyItRight applies auto-order logic using historical usage patterns and price/availability scanning. Orders are routed through PharmX, and when the default path fails or is suboptimal, the system can surface alternatives. In practice this turns PharmX into a hidden marketplace router: the pharmacist experiences “auto-ordering,” while PharmX experiences routed GTV.

Problems that pharmacies face

Out-of-stock problem workflow