Lately, I have been discovering some very interesting situations involving conglomerates that are trading at a substantial discount compared to their sum-of-the-parts valuations. I have also identified numerous opportunities in spun-out companies and have previously posted my investment theses on a few of them. In this article, I will provide a brief analysis of the three companies that were recently spun off from Vivendi: They appear cheap, but are they truly good long-term holdings?

Furthermore, I plan to delve into whether there is a valid reason behind these valuation discounts, and whether spun-out companies genuinely benefit from trading as independent entities.

Why do conglomerates trade at a discount to their net asset value (NAV)? This is the question we will explore in this article. I have published several reports on conglomerates that trade at substantial discounts to NAV, sometimes even below their current cash balances. For this reason, I believe it is worth explaining why the conglomerate discount exists and what steps companies can take to eliminate it.

The term conglomerate discount appears to have been coined by Michael Porter, who argued in 1987 that multibusiness companies are valued lower than the sum of their parts simply because they are conglomerates. Ever since, proponents of the conglomerate discount have maintained that individual businesses owned by conglomerates are often valued below pure-play companies operating in the same industry.

From my perspective, the existence of this discount makes sense, as investors may prefer to invest directly in individual companies rather than in a broad group operating across various sectors. Moreover, the complexity of conglomerate structures and the potential for mismanagement further contribute to these discounted valuations.

Let’s consider how investor sentiment toward conglomerates has evolved over time:

1960s–1970s: Conglomerates were widespread, and the idea of a conglomerate discount was less prominent. Diversification was viewed favorably because it helped mitigate risks and capitalize on growth opportunities in different industries.

1980s–1990s: The conglomerate discount became more evident as investors questioned the efficiency and managerial effectiveness of highly diversified companies. Concerns about a lack of focus, potential mismanagement, and the complexity of operations led to greater scrutiny and a tendency to value conglomerates at a discount.

2000s–Present: The trend toward deconglomeration accelerated, with many large conglomerates spinning off or divesting non-core businesses to enhance shareholder value. This shift was driven by the understanding that more focused companies often receive higher valuations. Consequently, it is common today to see conglomerate stock prices rise significantly when a spin-off or divestment is announced. The rise of activist investors, who are frequently critical of conglomerates and push for divestments or spin-offs, has further reinforced this trend.

We are currently in a market where many conglomerates, especially those operating internationally, are heavily penalized. Let’s consider what financial literature tells us about how to evaluate these companies.

A 2003 study titled “Diversification Discount or Premium?” by John D. Martin and Akin Sayrak investigated whether diversification leads to a discount or a premium in firm valuation. Their research used a short-term event study examining abnormal returns on the day of acquisition announcements. The study concluded there is often a premium associated with diversification, rather than a discount. However, it also highlighted that whether diversification results in a premium or a discount depends heavily on the specific time period under consideration.

The authors corroborated many findings from Moeller et al. (2004) regarding cumulative abnormal returns, the size effect, and the public status of the target. Their results showed that over the past decade, diversification carried a 1.07% premium. From 1985 to 1994, there was no significant premium or discount, yet from 1995 to 2005, a marked premium emerged. These outcomes align with earlier studies by Morck et al. (1990), Matsusaka (1993), and Klein (2001), who analyzed earlier periods (the 1960s and 1980s) and similarly concluded that a diversification discount or premium depends on the time frame observed.

There is also evidence that unrelated diversification can lead to a discount, while related diversification may command a premium. This makes sense when looking at successful conglomerates, such as TransDigm, which trade at a notable premium because of the value they add to acquired companies. In essence, the so-called “conglomerate discount” arises when the market believes that businesses under a single corporate umbrella generate lower returns than they would if operated independently. As a result, spin-offs and divestments are often seen as the preferred method of unlocking shareholder value and reducing the conglomerate discount. Indeed, conglomerates’ share prices frequently surge when they announce a “strategic plan to unlock value” for shareholders—reflecting the market’s current, rather short-term, mindset.

Nevertheless, many spin-offs are executed rapidly, pressured by market forces, which can leave the new entity with insufficient time to prepare robust investor presentations or establish clear expectations. As a result, many spin-off companies experience significant sell-offs on their first day of trading as investors rush to cash out immediately, overshadowing the long-term potential these newly independent firms might hold.

How can we, as long-term value investors, profit from this situation?

There are two main opportunities:

Conglomerates trading at a discount

Spun-off companies

1. Conglomerates Trading at a Huge Discount

Some conglomerates are currently valued at a significant discount to their net asset value (NAV). However, it’s crucial to identify potential catalysts that could unlock this value. The most common catalysts are:

Spin-offs

Dividends (often funded by asset sales or subsidiary divestments)

Here’s why a spin-off or divestment can be so powerful: If a conglomerate is trading at 50% of its NAV, and it spins off or divests an asset, that asset might then be valued at 100% of its fair value in the market (this may take time for spin-offs). That means, as a shareholder, you effectively capture a doubling in the value of that piece of the business—from 50% inside the conglomerate to 100% as a separate entity.

Additionally, the overall NAV discount may narrow if the market sees the conglomerate making clear moves to reduce it. However, if you plan on holding a conglomerate long-term, ensure not only that the sum-of-the-parts valuation is significantly higher than the market cap, but also that the company isn’t destroying value by holding onto numerous subsidiaries.

2. Spun-Off Companies

In theory, spin-offs should unlock value. In reality, many are done hastily, with minimal preparation. Newly spun-off companies often trade at “fire sale” prices because existing shareholders—who bought in mainly for the discount to NAV—tend to sell their shares as soon as the spin-off occurs.

This creates a potential opportunity: if you’re prepared to do the research—digging into SEC filings, comparing the parent’s older reports with the newly released data from the standalone company—you may discover excellent businesses at extremely attractive valuations. Of course, this carries added risk: you’re investing based on the future potential of a newly independent company rather than its historical track record. Still, for those willing to look closely at the fundamentals and the prospects of a spin-off, the rewards can be significant.

For the reasons mentioned above, spin-offs have often outperformed the broader indexes. When it comes to finding these potentially attractive spun-out companies, I focus on those spun off hastily, in what I would call a “fire listing,” where poor management decisions lead to an asset being listed at a bargain price just so they can claim to have “unlocked shareholder value.” Remember that my earlier math assumes a patient and deliberate spin-off process, which is not the norm—many managers simply list a division at a low valuation, and insiders later buy the discounted stock for their own benefit. In cases I find intriguing, I try to do exactly what those insiders and big shareholders do: purchase the spun-out stock at an extremely cheap price, taking advantage of minimal coverage and the absence of comprehensive presentations or well-prepared investor reports. Often, we only have an admission filing of 500+ pages, which is a daunting but worthwhile challenge for serious value investors. My work on Optima Health was a prime example of this approach.

After laying out this background, I usually go into the details of which conglomerates and spin-offs appear promising, and the same will apply here as I move on to the analysis of Vivendi’s newly spun-out businesses. But before discussing the pieces of Vivendi, let’s highlight some notable cases I’ve encountered in the market. On the conglomerate side, two names worth mentioning are Grupo San Jose and Libertas, both trading at large NAV discounts for various reasons—among them, the general “conglomerate discount.” I believe this discount is unwarranted in their cases, and in fact they might deserve a slight premium. Both operate in real estate and construction (sectors notoriously sensitive to macroeconomic shifts) and have diversified into well-managed business lines to stabilize operations. They also maintain significant cash and liquid assets to sustain and grow these endeavors. Coupled with conservative, experienced management, each should at least be valued at the sum of its parts.

Turning to spin-offs, there are plenty of compelling examples. Some companies I’ve covered resulted from hasty spin-offs, now trading at very low valuations due to negligible analyst coverage and a lack of formal investor presentations. I see enormous potential in these situations, since independent management teams tend to be more aligned with shareholder interests, particularly when their compensation is tied to the company’s stock performance. If you buy into these lesser-known spin-offs before the broader market discovers them, you can benefit substantially, especially when former shareholders of the parent are selling these new shares en masse. Two companies that fit this pattern are Optima Health and Seaport Entertainment.

I have also been watching Vivendi’s recent spin-offs—Louis Lafayette, Canal+, and Havas. Each appears cheap based on standard valuation metrics, but I’m specifically interested in companies that stand to benefit from operating independently and have a high likelihood of appealing to the market over time. I will now provide a quick summary of each of these Vivendi spin-outs and share my take on which ones deserve a more detailed exploration.

Canal +

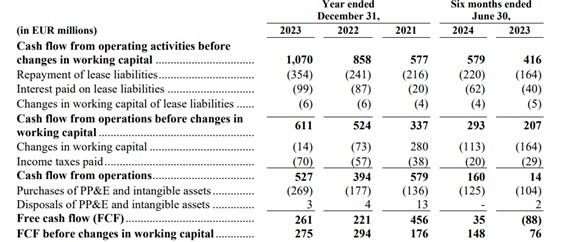

Canal+ is a French media business that derives 53% of its revenue from France, 23% from Europe, 17% from Africa and EMEA, and the rest from content production. After its initial listing at 230 pence, the share price fell by about 20%. The company has 992 million shares outstanding at a share price of 192 pence, giving it a market capitalization of 1.9 billion pounds (approximately 2.37 billion dollars). With 6.2 billion dollars in revenue, nearly half a billion in EBITDA, and solid cash flow conversion, Canal+ looks inexpensive from a multiples perspective.

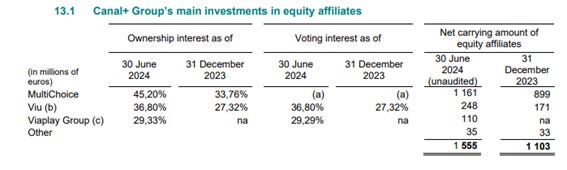

The company has 26.8 million subscribers and more than 400 million monthly active users. It is the number-one pay TV provider in 20 countries, with a strong and growing presence in Africa. Canal+ also holds significant equity stakes in international media companies, reflected by 1.55 billion on its books as of June 30, 2024, through investments in Multichoice, Viu, and Viaplay Group.

A noteworthy development is the plan to acquire the remaining shares of Multichoice at 125 ZAR, or about 6.79 dollars per share. This transaction will increase Canal+’s exposure to Africa to over half of its total revenues. However, the company acknowledges that this market brings certain risks, such as electricity shortages, load-shedding, and potential delays in infrastructure. Multichoice itself has struggled to grow revenues for a decade and maintains volatile margins. Its EBITDA typically hovers around 500 million, and at an enterprise value of 3.2 billion, Canal+ would be paying a multiple of about 6. Since this is not a comprehensive analysis, I have not deeply examined potential synergies.

After the deal, Canal+ could see EBITDA rise to between 800 and 900 million, and with the acquisition adding 1.6 billion in debt (plus Multichoice’s existing debt), the enterprise value might reach around 5 billion. This implies somewhat high leverage, and while the company trades at a cheap valuation, it does not seem positioned for strong growth. It is reminiscent of Warner Bros. Discovery, which also grapples with high debt and limited growth but holds valuable assets. Personally, I do not find Canal+ compelling as a long-term investment at the moment, though it might become more interesting if synergies emerge or if analyst coverage increases.

Louis Hachete.

Louis Hachette has fared the best among Vivendi’s spin-offs. Initially listed at around €1.12 per share, it climbed to over €1.50 before cooling off, in part due to a lack of clear investor relations, overly complex filings, and a convoluted financial structure. To simplify matters, Louis Hachette Group is a holding company that emerged from a partial spin-off of Vivendi, consolidating majority stakes in Lagardère SA (66.6%) and Prisma Media S.A.S. (100%).

Within Lagardère, the two main segments are Lagardère Publishing (Hachette Livre) and Lagardère Travel Retail. Lagardère Publishing is a top player in general consumer books, with strong footholds in France, the UK, Spain, and the United States, generating roughly €2.5–3 billion in annual revenue. Lagardère Travel Retail, on the other hand, operates over 5,000 stores and restaurants in travel hubs worldwide, contributing more than €5 billion in yearly revenue. Prisma Media specializes in magazines and online media. Beyond these, the group has additional media and entertainment ventures, covering newspaper publishing, broadcasting, and event management.

Since emerging from the pandemic, the company’s revenues have steadily recovered, reaching €8.4 billion in FY 2023. The first nine months of 2024 show around 10% year-over-year growth. However, EBIT margins remain slim at around 4%, with about €346 million in EBIT for FY 2024. On a pro forma basis, EBITA stands closer to €500 million, yet net income amounts to only €45 million. Over the trailing twelve months, EBITDA reached roughly €779 million.

The main concern lies in the debt load. Lagardère itself holds €2 billion in debt, of which roughly two-thirds (or €1.33 billion) can be attributed to Louis Hachette’s stake. Beyond that, Louis Hachette carries an additional €1.5 billion in debt on its own balance sheet. The company has stated it will focus on debt repayment and plans to distribute 85% of any dividends received from its subsidiaries to Louis Hachette’s shareholders. The group’s annual cash flow hovers between €200 million and €300 million. Although interest payments appear manageable and cash flow is higher than reported net income—owing to large depreciation and amortization expenses—the substantial debt remains a significant overhang.

Louis Hachette’s debt agreement with Vivendi also places a ceiling on possible dividend payouts until this obligation is cleared. The limits range from €92 million for 2024 up to €190 million for 2028. If the company pays out the maximum allowed dividends, the current yield could be around 7%, potentially rising to 14% by 2028. Nonetheless, substantial growth seems unlikely; the business has likely already benefitted from the post-COVID rebound, and any further expansion will likely hover in the low to mid-single digits.

While Louis Hachette screens inexpensively based on EBITDA, its high leverage and modest free cash flow growth do not make it particularly appealing. At the moment, it does not appear that operating as a standalone entity offers a clear advantage. As a result, I currently view Louis Hachette as a pass rather than a compelling long-term opportunity.

HAVAS

Havas stands out as an intriguing spin-off with no debt, EBIT margins around 10%, and mid-single-digit revenue growth prospects fueled partly by ongoing acquisitions. It currently has a market cap of around €1.54 billion and an enterprise value close to €1.34 billion, based on its latest guidance for net cash. With EBIT expected to land between €335 million and €340 million, Havas appears to be trading at roughly four times EBIT and has a healthy balance sheet, positioning it well for future expansion.

The company is headquartered in Paris and is one of the world’s largest and most established global communications and marketing groups. It offers end-to-end services across the advertising value chain, with diversified exposure to multiple industry verticals and geographies. Employing over 23,000 people and operating in more than 100 markets, Havas has consistently reinvented itself to drive change in the industry and anticipate emerging business needs.

Its net revenue breakdown for 2023 includes approximately 39% from Havas Creative, 36% from Havas Media, and 24% from Havas Health. The company has seen especially strong growth in Latin America and Asia. A serial acquirer, Havas typically purchases five to ten companies a year and expects annual top-line growth to benefit an additional 1.5% through acquisitions. Overall, its revenue has increased at around 4.5% per year on average since 2018—2.1% organically and the rest via acquisitions—while EBITDA margins have improved by 130 basis points over the same period. Cash flow stands at about €300 million per year on average, with conversion rising over the past six years.

As a service-oriented company, Havas’s revenue concentration is worth examining. For the year ended December 31, 2023, and the six months ended June 30, 2024, its largest client accounted for 7.7% and 8.4% of net revenue, respectively. The top ten clients represented 21.7% and 20.2% in those same periods. While there has been some impact from losing a major client in 2024, this does not appear to be a long-term concern given the company’s breadth of services and historical growth trajectory.

Even if top-line growth remains modest, the potential for further margin expansion could boost bottom-line results. With a clean balance sheet, trading at roughly four to five times free cash flow, and moderate growth prospects, Havas looks poised for a market re-rating—particularly if it resumes or increases dividend payments. Judging by historical practice, the company could distribute dividends near or slightly below €100 million, translating to a yield around 7–8%. In my view, Havas is the most compelling of the recent Vivendi spin-offs, and I believe it warrants a closer look. I plan to publish a more detailed analysis for paid subscribers, so stay tuned if you are interested in the full investment thesis.

Conclusion

Overall, I believe that spin-offs and conglomerates are excellent sources of mispriced equities in today’s markets, especially outside the United States. However, it is crucial to focus on specific catalysts when investing in a conglomerate—such as spin-offs, dividends, or strategic divestments—and, on the spin-off side, to look for businesses with genuine long-term compounding potential.

In my view, Canal+ and Louis Hachette do not appear particularly attractive at this point, but Havas stands out as a compelling opportunity. This pattern is common when assessing spin-offs: most are not appealing, but if you are willing to do the in-depth research and analysis, you can occasionally uncover a hidden gem.

I appreciate as a spin-off the Havas shares were distributed to Vivendi shareholders (and that could explain the drop after listing as they cashed in) but I don’t understand why the price was set as low as €1.80 - at 5 times free cashflow. Having looked at the Prospectus - and the company seems confident in its strategy and growth prospects - I have made an initial purchase.

Vivendi itself is offcourse the real gem with significant undervaluation relative to its sharepositions in umg and telefonica italia